VELUX

At VELUX on 17 September 2025, Postdoc and PhD Heidi Sørensen Merrild presented her new article on regenerative architecture at the event Exchange for Change, held in connection with the opening of LKR Innovation House in Østbirk.

“Experiences from a Transformation – LKR Innovation House”

How can architecture not only reduce its impact on climate and nature, but actively contribute to restoring and strengthening ecosystems, material cycles, and social communities? This question forms the core of a new article by postdoc and PhD Heidi Merrild, presented at VELUX on 17 September during the Exchange for Change event.

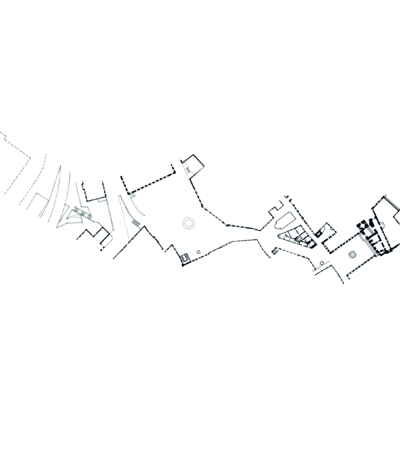

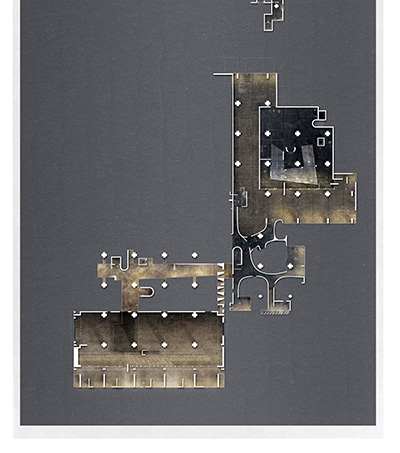

LKR Innovation House is analysed as a central case, with particular potential to demonstrate pathways towards a regenerative practice. The analysis addresses environmental impact, circularity, biodiversity, site-specific conditions, as well as social and political aspects.

A key element of the article is the communication of the knowledge and methods generated through research. The first part consists of a mapping of the project and the elements pointing towards construction with “almost zero” environmental impact and a new regenerative practice. The focus is on environmental impact, site-specific conditions, circularity and reuse, as well as ethical, social, and political dimensions – and not least detailing and architectural quality.

The second part examines the concrete barriers to the green transition and the newly adopted CO₂ framework for future construction. Through interviews, both readiness and specific challenges in the transition to regenerative building practices are mapped.

Finally, the article presents a future scenario for regenerative construction.

Ten Key Takeaways from LKR Innovation House

In the article “Experiences from a Transformation”, Heidi Merrild outlines ten key points that summarise the article and the LKR Innovation House project:

Point 1: Freedom to Innovate

When transforming a building and opening it up, you never know what you will encounter. Each project is unique and may present unforeseen challenges, requiring preparedness for the unexpected. Rather than imposing drawings created at a distance or from above, we must learn from what emerges as we open the building and sense the materials. This approach allows for closer investigation of buildings and materials, as opposed to a detached perspective. It is a design or transformation process not bound by fixed, measurable sustainability parameters, keeping possibilities open and allowing greater creativity.

Point 2: Sharing Risk

Experimentation entails increased risk. Transformation requires a new model for sharing risk and a collective approach to developing new solutions. Creating such solutions demands testing and flexibility, but this is a costly process that calls for rethinking rules and standards. Open frameworks are needed when experimenting and shaping future solutions. As this is a risky process, a model for distributing costs is essential.

Point 3: Nature and Biodiversity

Transformation is intrinsically linked to biodiversity. Soil itself is a valuable material. The atmosphere must have access to the soil so plants can grow. We must uncover sealed surfaces, break up paving, dissolve boundaries, and connect species. Transformation creates openness in existing cities and buildings and reconnects architecture with the landscape. By breaking hard, closed boundaries and surfaces, we not only preserve what exists – nature, buildings, and cities – but also add new species and create diversity. We must stop relocating soil and instead regard it as a valuable resource. Experiential and sensory mapping should be trusted, and biodiversity must be included in our calculations.

Point 4: Everything Comes from Somewhere

How are materials brought to life? What are their historical uses and conditions? How do they behave physically on site, and how are they connected? We must map existing materials and local contexts and create new narratives that follow materials through their production and transformation. We should build on what already exists and create new readings of places and their inherent potential, in collaboration with other disciplines using diverse methods and approaches.

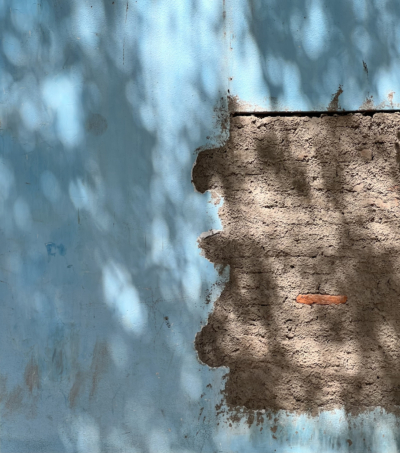

Point 5: Conservation and Reuse

Time and weather affect materials. Some deteriorate, while others become more beautiful with age. Frugality responds to the need for reorientation and for minimising, reusing, and recycling. Time and making are integral to the circularity of craftsmanship and detailing, requiring trust in materials and their patination over time. Though demanding, recognising the value of existing materials and their inherent qualities pays off.

Point 6: Embodied Energy

Too much focus has been placed on reducing operational energy, while the value of embodied energy in materials and building components has been overlooked. We must utilise the energy already embedded in existing materials. There is an ethical dimension to not demolishing and rebuilding. A new basis for evaluating materials in relation to operation and maintenance is needed. Existing materials may create friction in everyday comfort, but reuse saves energy and represents sound judgement.

Point 7: “New” Materials

Resource- and process-intensive materials must be phased out, and it should be easier to test and certify new materials. Introducing biogenic materials requires testing, which is currently too time-consuming, costly, and complex. Certification processes are particularly burdensome for small start-ups. Alternative testing solutions and international experiences must be considered, alongside new regulatory frameworks that are more accommodating or flexible towards biogenic materials.

Point 8: Time for Change

In the future, cities and architecture should be perceived as textiles we continue to embroider. We inherit our surroundings and steward them forward. Traditionally, significant architecture has been seen as a static Gesamtkunstwerk. We must instead create architecture that future generations can build upon.

Point 9: A World of Light and Air

Architecture was revolutionised when light entered buildings. The introduction of roof windows enabled attic spaces to be used. The intertwining of light and air creates inhabitable spaces both indoors and outdoors. Mechanical ventilation has become the norm because control and measurement are preferred over trusting “natural” processes with fluctuations and seasonal variations. While this introduces friction in comfort, it creates living buildings and strengthens the relationship between inside and outside. Comfort is largely culturally constructed, shaped by expectations and routines.

Point 10: New Depth and Greater Density

We must listen to places and sense their inherent narratives, create new connections and species, break down boundaries, and open sealed surfaces. Locally, we must work with new forms of depth and density, moving away from viewing areas as isolated zones – industrial areas, suburban housing, and production landscapes. Human and non-human resources must be seen as interwoven. The more connections, the greater the depth and density.

The article can be read via this link.